A training sidebar from the AIP series, if you’re preparing to engage in high-intensity physical activity.

If you’re holding a ticket that says “Yes, I’m at least 40,” while standing in the line for Those who still wanna go all out, here is a single post summary of everything I’ve learned so far in my return to martial arts as a nearly 60-year-old physician. The transition from a low-key daily routine — lots of typing, thinking, and talking — to Brazilian jiu-jitsu’s sweating, throwing, and grappling was marred by early injuries.

If your activity of choice involves intense exertion that can take you to the limit of what your body can perform — dance, tennis, or competition of any kind — consider adapting the following insights.

1. Develop a solo training base

Even if you train at an established school or facility, those businesses can get shut down during pandemic surges. A training program that you develop for yourself is the essential prehab/rehab regimen that I’ve described previously: depending on you alone with training tools readily at hand, augmented with specifics once the connective tissue base (3-6 months) has been established.

The leap from here to the mat (or court, or floor, or pole) should be short, if you drill and strengthen fundamentals. Regular training is a keystone to reducing injury risks, so it pays to have a training base that you can’t be deprived of by developments outside your control (including more injuries).

2. Address COVID at home

This contagious, infectious disease has the potential to seriously affect you and members of your home. Do what you can to minimize the risk of training disruption because you or someone close gets waylaid for weeks, months, or worse (translation: masks and vaccinating, particularly for vulnerable older and less healthy family members).

Real life commonly disrupts training momentum and longevity: kids, finances, relocation, in-laws, workplace restructuring, etc. It doesn’t get more real and disruptive than death.

3. Consider COVID where you train

If your coach or crew is open to the question, think about whether immunization status will affect your decision to train — maybe certain days/classes with fewer people, or more vaccinated partners? Maybe going fewer sessions per week? 2 sessions vs. 3 sessions per week is a 33% reduction in potential exposure.

Or not. But remember, mat sparring and group activities are awesome ways to spread the Delta variant amongst unvaccinated, panting partners. I was feeling cautiously optimistic that I hadn’t heard of a superspreader event among BJJ schools…then a local college football team (different but similar training sessions) had an outbreak infecting TEN players.

Translation: you can reduce your risk if your group is open to working on it, but training outside your known family means accepting a certain exposure risk.

4. Gird your illness-fighting loins

Heading into Halloween and the holidays, especially with a drop in mask usage, you’ve probably noticed more people coughing in public places, how could you not?

Some people never seem to get sick with coughs, colds, or flus. I’ve adopted vitamin D, zinc (pills, lozenges, and pre-workout nasal sprays), elderberry, and sleep and stress management measures based on Chris Masterjohn’s comprehensive review of using supplements to buff your immune system.

And don’t forget the fundamental and non-interchangeable pillars underlying immune and general health: nutrition, sleep (less than 6 hours significantly increases the odds of catching a cold compared to 7 or more hours of nightly sleep), stress management, physical activity, socialization, and circadian alignment.

Again, there’s mask use when in public. I can confirm that when doctors were plenty stressed and overworked at the height of the pandemic, we didn’t get our usual 2+ per year episodes of respiratory infections while wearing masks in a virus-rich environment. I know medical staff who’ve gotten COVID infections but none from workplace exposure, all from going out in public, without masks.

5. Project your mind far afield

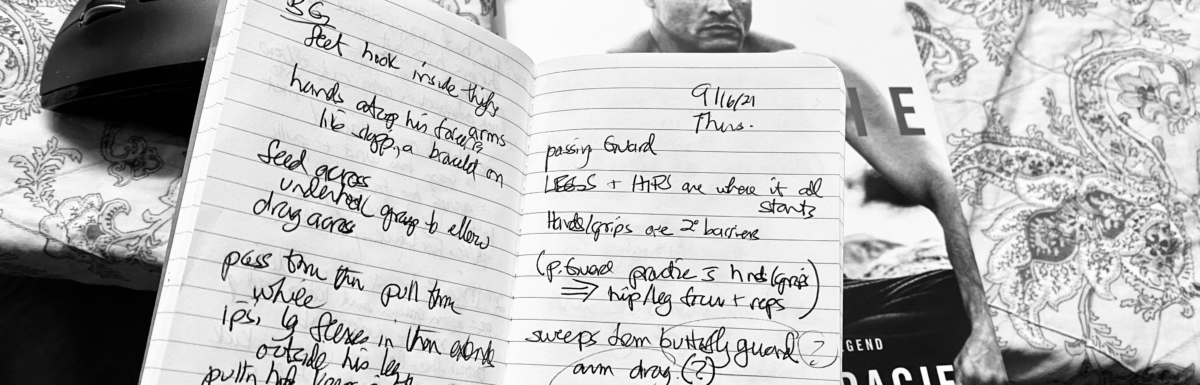

If you’re into Brazilian jiu-jitsu and want to brush up on Position, Connection, Pressure, or other technical points, there’s Rickson Gracie’s online university. Self-defense? Videos by Paul Sharp via BJJ Fanatics, or Burt Richardson. Kesa gatame and side mount attacks? CSW videos by Eric Paulson, Henry Aikins’ series on BJJ Fanatics, or the kesa gatame kill system by Coach Tom and The Grappling Academy.

In other words, there are more audiovisual learning opportunities in the modern information era than ever before in the history of humankind. YouTube is the 2nd largest search engine on Earth.

You’re not going to learn kung fu by watching videos, but you know by now when an instructor resonates with you (one of the prime advantages of being 40+). Once you’re less worried about breaking off bits and derailing your training, it’s natural to become interested in learning to get better. You’ll gravitate towards certain sources, get ideas, and enrich your proverbial soup base.

6. Consider private sessions with a coach

Again, this was the best, most overdue decision I ever made clawing my way back to full-intensity practice. Because of that guidance, I’m in Month 2 of group classes, which end with 15 minutes of careful but intense sparring and rotating partners, compared to being sidelined with muscle and ligament tears doing basic drills within the first two weeks of previous returns.

I thought I knew enough as a sports medicine physician to guide my own return.

Translation: Just get the private training, already.

Preferably from a coach who is in their 4th decade or older, or who trains a cohort that resembles you. If you’ve decided that ongoing high-intensity participation is important to you, you’re in your 4th+ decade, and coming back from a hiatus, the gap between what you think you can do and what you don’t know you’ve lost is so startlingly large…just get the private guidance.

7. Prioritize finding/developing a solid training crew

If your activity of choice involves playing with others, then after working with a coach, the next highest priority is finding a regular training group. A trustworthy crew will a) work your body, mind, and spirit comprehensively, and b) get your mind accustomed to the challenges of group participation and — surprise! — surviving each class when every early session is a struggle.

You’re developing a very positive habit: starting out, everyone else is better than you, nothing works and you don’t know what you’re supposed to be doing, but with every class (and private lesson) you learn a bit more, you apply a bit more, and most importantly you survive each and every class.

You’re struggling yet you come out the other side, and every night you go this is the practice. You survive, you survive, you survive, and your brain starts to get it: this is OK. And the learning starts soaking in.

8. If possible, drill

The next level beyond not-getting-broken is getting better, which means learning new ways of moving better, and then smoothing out your moves so they can be applied on demand without hesitation. Classes and privates break down and transmit the former but may not offer enough repetition to efficiently develop the latter, particularly if your activity depends more on technique than conditioning.

If you consistently attend classes, you’ll eventually rep out the material to get it in your bones. But if you drill the moves repeatedly — with a partner, training aid, or solo — that incorporation will happen sooner, and free up your CPU to focus on broader issues (like strategy for combat or competitive sports, or style for performance arts).

Leave a Reply