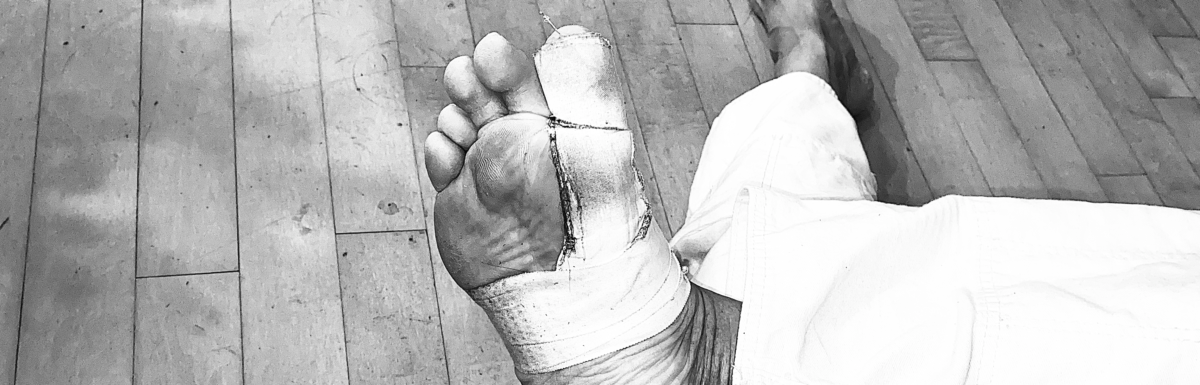

Some time last month, I passed the 6-month mark of being back on the mat doing moderately intense martial arts — Brazilian jiu-jitsu — without major injury. Not that I’m superstitious…but there’s no need to state the exact date, and I refuse to surrender my lucky t-shirt.

The more vigorous the activity and the longer your time away from it, the greater the risk of injury on your return.

While I’m always mindful of sidelining injuries, uninterrupted training has allowed my focus to change. Like moving through Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, I’ve begun looking past Don’t get hurt towards higher goals. What’s the next thing I can learn? I get abc, and the more advanced xyz sequence still seems like Martian dance choreography. But efg suddenly makes sense. Fine-tuning is a thing. The arms and legs go here, but here’s this little shift that smears your partner ten times harder into the mat, like cream cheese spackled on a bagel by a pissed-off deli worker.

Details hidden in the so-called basics. Just waiting to be uncovered on a more patient, repeat go-around.

The ultimate

I’ve also been rethinking the objective of martial arts training. Not inner peace or harmony with the universe — I’ve got those (kidding) — but rather, true self-defense preparedness. Ending each class with 15 minutes of sparring was an eye-opener.

In the modern martial arts, that’s often an oddly neglected aspect of training. If your endgame isn’t a competition award but surviving an altercation where someone is doing their darnedest to pound you, the list of Critical Things To Know shortens drastically. Yet most martial arts training does not look like this:

- Gross motor movements that are preserved under extreme stress

- Actions that curb or eliminate an assailant’s attacks

- Escaping

It should be less about flashy moves to persuade folks to sign up than basic drills to drive an assailant down a narrow, hard chute that you’re familiar with. And most critically, including practice that eventually involves all-out efforts on both sides.

Sparring, regardless of the martial art, develops a critical quality: not losing your shit when everyone’s going bananas. How many exposures to physical intensity do most people have? The great Rickson Gracie refers to this as Getting comfortable with discomfort, or as he put it, “Finding whatever comfort you can in hell.” When defending your life, this includes powering through failure to the next option, with Tasmanian Devil tenacity.

Technical instruction gives you the tools to be intense and tenacious. Tool PROFICIENCY + intensity & tenacity = pretty good chance of prevailing.

Achieving the ultimate

All of the above has an underlying prerequisite.

Regular training.

You get proficient at moves by drilling them repeatedly, aka regular training.

You become able to train at high intensity by gradually adapting to higher workout intensity, built-up through regular training.

Likewise, you become comfortable with people coming at you, and you yourself going all-out, by incorporating carefully designed all-out sessions into your classes. Again, through regular training.

Developing anything of consequence beyond Gee, this seems kinda cool never happens if your training keeps stalling after a few weeks.

Whether or not you want to do jiu-jitsu safely beyond your 6th decade, this is a great example of consistency being key to achieving health and fitness goals. In the modern era’s return to Panem et circenses, being consistent is rare, and impulsivity is the more common norm.

Which is why, if you can dial-in consistency, your results will be nothing short of extraordinary.

Leave a Reply